Why I am Against the Government’s Proposal to Criminalize “fake news” – and Why (I think) You Should be Too

Don’t get me wrong, disinformation1 can have profound consequences on our country, including our respect for democracy, diversity and human rights. Our own work at Hashtag Generation has documented2 how harmful narratives that have potential to skew public opinion and affect healthy debate circulate in online and offline spaces. The term “going viral” is based on the way that viruses spread and just like a virus that spreads across the body, false news can also self-replicate and reverberate across the body politic. There’s no disagreement on this. In fact, I agree with the state’s proposition that disinformation can have profound impacts on our country’s electoral and extra-electoral politics. For instance, it is now widely acknowledged that the Government’s forced cremation policy was based on discredited disinformation. While the policy has now been revoked, there has been no apology for, let alone an acknowledgement of the tremendous pain and hurt the policy caused many people, especially the Muslim community for almost a year. This is also why, in the past five years my colleagues and I have also spoken to thousands of Sri Lankans from all walks of life on consuming the content they come across, especially on social media platforms and instant messaging applications, more critically. Why then am I not (along with others)3 delighted at the prospect of the Sri Lankan state adopting a new law on disinformation? This short(ish) piece is my attempt to shed some light on this question.

While many would feel the need to turn to the law to address any social ill, my suggestion is that the law (or more laws, as I will point out that certain sections of existing laws already cover types of disinformation) is not always a solution. In fact, sometimes it can be a problem. In Sri Lanka (as elsewhere) the law is not always a neutral tool. While the law is meant to make us feel safer, for some people, for example in Sri Lanka for queer people4 and sex workers5, the law (among other things) is what makes their lives increasingly difficult.

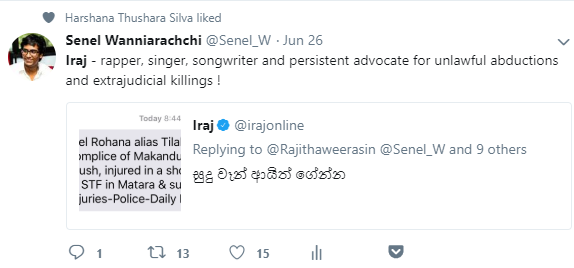

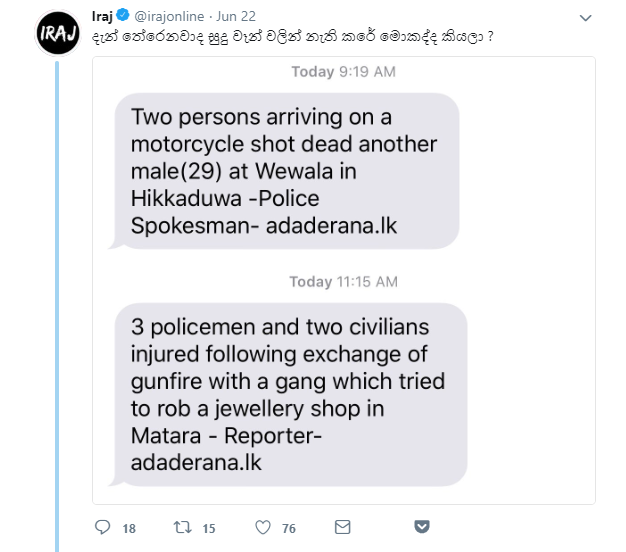

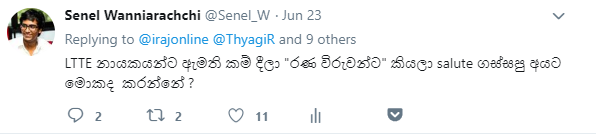

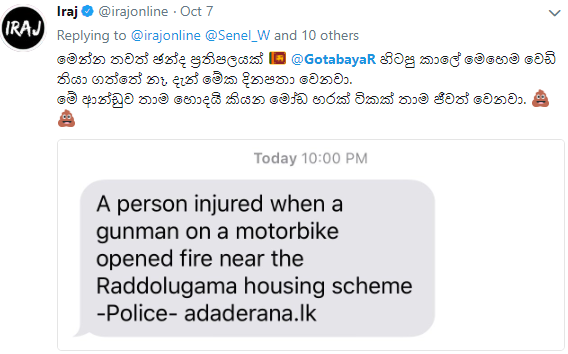

Just like falsehood goes viral, the truth can also be stubbornly self-replicating. Tyrants and despots everywhere fear this stubborn quality of truth. This means that content that is seen as embarrassing or damaging to a government (including future governments) can be open to being labelled “fake news” and the disseminators on such content will be at risk of facing criminal sanction, including jail time. This could have profound impacts on the freedom of expression, media freedom and the civic space in the country.

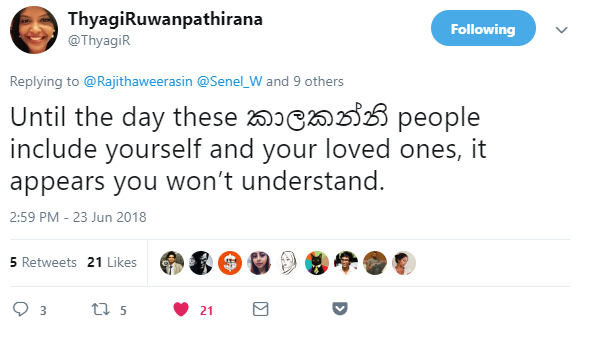

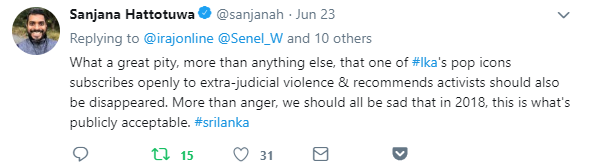

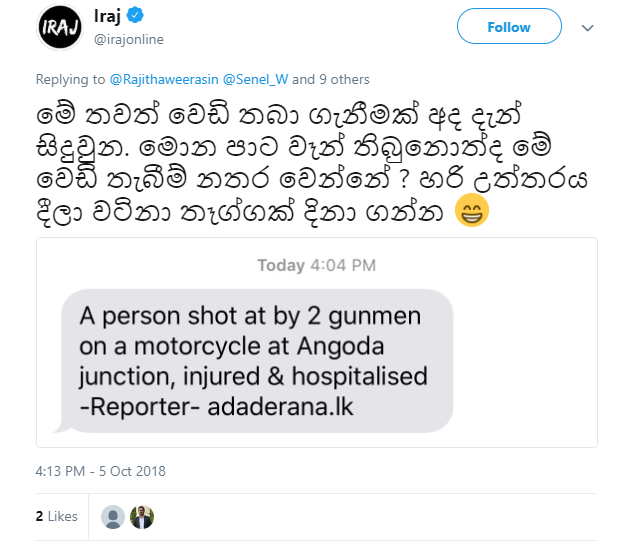

This is not just reactionary fear-mongering (not that there is anything “just” about fear-mongering). While sections in the law as it stands now already curtail the freedom of expression6 on different grounds including types of disinformation and hate speech; the way some of these provisions have been invoked by the police in the past7 provides some perspective on how a prospective “fake news law” may be deployed.

Author Shakthika Sathkumara was arrested in April 2019 (when the previous “Good Governance” Government was in power) under the ICCPR Act and the Penal Code for a work of fiction that involves a story of sexual abuse taking place in a Buddhist temple. Sathkumara was detained for 130 days. He was eventually discharged8 earlier this year with no apology. Meanwhile, Abdul Raheem Masaheena9 was arrested under the ICCPR Act for wearing a dress with the design of a ship’s helm on allegations that it resembled the dharmachakra. Ramzy Razeek, a retired government officer, was reportedly arrested under the ICCPR Act and Computer Crimes Act for calling for an “ideological jihad” against anti-Muslim hate10. Naomi Michelle Coleman, a British citizen was arrested and subsequently deported under the Penal code for having a tattoo of Lord Buddha on her arm11. Later, the Supreme Court observed that there was no reasonable basis for the arrest.

As I write, (today is the 12th of June 2021) Hejaaz Hizbullah, a prominent lawyer remains in custody under vague charges of “inciting communal disharmony”12. Furthermore, Ahnaf Jazeem, a poet and a teacher is being detained under the Prevention of Terrorism Act (PTA) for penning an anthology of poetry called Navarasam13.

Meanwhile, during Covid-19 response, an individual was reportedly arrested for criticising the appointment of former MP Basil Rajapaksa as the head of the Presidential Task Force on COVID-1914. Similarly, an individual was arrested for using Facebook to criticise a Divisional Secretariat Officer for ‘injustices’ committed during the quarantine programme15. While I’ve reduced these to “cases” here to further my own argument, these are all human beings with fears, aspirations and loved one’s who worry about them.

We shouldn’t forget that these developments in Sri Lanka are taking place within a global backdrop of states weaponizing the Covid-19 Pandemic in order to suppress freedom of expression.

Around the world, laws which were purportedly passed to “crack down on fake news” have led to similar consequences. For example, Singapore16, Malaysia17 and Russia18 have been accused of using their respective anti-fake news laws to further stifle free speech, especially criticism of the government. In Germany, the Association of Journalists has complained that social media companies are being too cautious and refuse to publish anything that could be interpreted under their own fake news law.

Picture a central tower in a prison with a guard19. The prisoners can’t see the tower themselves so they won’t know whether they are being watched at any given time or not. The result is that they internalize the surveillance so much that they modify their behaviour as if they were being watched all the time because of the unverifiable potentiality that they just might be. The power of such a “disciplinary gaze” lies in the fact that it controls our behaviour even when it is not actually turned on us.

Whenever governments get involved in policing expression – even for seemingly well-intended reasons – there is always a lack of trust in the process. Particularly, in contexts like Sri Lanka, where the law has been used as a tool to stifle free expression and the “mainstream”20 press is often hyper-partisan.

If one really wants to “crack down on fake news”, my suggestion is to go back to school. In schools across Sri Lanka, children are learning the evolution of computing from large mainframe computers and are acquiring skills like using the MS Office Packages as part of their ICT curricula. While this is all important, we need to provide our children (and adults) with critical media literacy skills. Furthermore, the state should also work towards healing the deep seated divisions and social fault lines among communities in Sri Lanka. These are the biggest drivers of rumour and conspiracy that permeate in our society. Contemporaneously, we need to support and strengthen independent fact-checking and investigative journalism initiatives as well as citizen-led initiatives that generate behaviourally-informed counter and alternative messages to online hate speech and disinformation, not stifle them. Finally, we also need to keep demanding that the giant social media companies enforce the Community Standards they have already committed to upholding globally. In these testing times, we should strive towards creating the kind of world we want to collectively inhabit. For some of us, “in the world we want, everybody fits. The world we want is a world in which many worlds fit.”

—

- While there are important discussions to be had on what constitutes disinformation and what the term really means, I will not engage with these in this short piece. For some important analysis on this, please see Gehan Gunathilake (2021) https://groundviews.org/2021/05/26/criminalising-disinformation-neither-the-time-nor-the-place/

- See https://hashtaggeneration.org/publications/

- See statements issued by the Free Media Movement https://ifex.org/sri-lanka-free-media-movement-said-fake-news-bill-could-undermine-freedom-of-expression/, the Bar Association of Sri Lanka https://economynext.com/police-could-misuse-fake-news-allegations-to-stifle-free-speech-sri-lanka-bar-association-82932/

- See Sections 365 and 365A of Sri Lanka’s Penal Code. 1885. Available at http://hrlibrary.umn.edu/research/srilanka/statutes/Penal_Code.pdf

- See Sri Lanka’s Vagrants Ordinance. 1842. Available at http://hrlibrary.umn.edu/research/srilanka/statutes/Vagrants_Ordinance.pdf and Brothels Ordinance. 1889. Available at https://www.lawnet.gov.lk/brothels-3/

- These include the The Constitution, The Penal Code, Parliament (Powers and Privileges) Act, No. 21 of 1953, International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR) Act, No. 56 of 2007, Police Ordinance (Chapter 53), Prevention of Terrorism (Temporary Provisions) Act, No. 48 of 1979, Public Security Ordinance No. 25 of 1947 , Official Secrets Act, No. 32 of 1955, Obscene Publications Ordinance, No. 4 of 1927, Prevention of Domestic Violence Act, No. 34 of 2005, Computer Crimes Act, No. 24 of 2007, Intellectual Property Act, No. 36 of 2003, Information and Communication Technology Act, No. 27 of 2003 and Sri Lanka Telecommunications Act (SLTA), No. 25 of 1991 and the Bail Act , No. 30 of 1997.

- These cases, among others were compiled by Verite Research and Democracy reporting International in the Report Regulating Social Media in Sri Lanka: Formal and Alternative Mechanisms. See presentation of findings https://www.facebook.com/watch/live/?v=910244689780435&ref=watch_permalink

- See https://economynext.com/shakthika-sathkumara-discharged-days-ahead-of-unhrc-sessions-78661/

- See https://www.hrw.org/news/2019/07/03/sri-lanka-muslims-face-threats-attacks

- See https://groundviews.org/2020/05/12/ramzy-razeek-an-extraordinary-struggle-for-an-ordinary-life-of-service-upended-by-an-arrest/

- See https://www.bbc.com/news/world-asia-27107857

- See https://www.srilankacampaign.org/a-year-on-hejaaz-hizbullah-still-imprisoned/

- See https://ifex.org/sri-lanka-groups-call-for-release-of-poet-ahnaf-jazeem-detained-for-a-year-without-charge/

- See https://www.wsws.org/en/articles/2020/04/09/medi-a09.html

- Ibid

- See https://www.hrw.org/news/2021/01/13/singapore-fake-news-law-curtails-speech

- See https://www.hrw.org/news/2021/03/13/malaysia-revoke-fake-news-ordinance

- See https://ipi.media/new-fake-news-law-stifles-independent-reporting-in-russia-on-covid-19/

- See https://ethics.org.au/ethics-explainer-panopticon-what-is-the-panopticon-effect/#:~:text=The%20panopticon%20is%20a%20disciplinary,not%20they%20are%20being%20watched.

- I used mainstream within inverted commas here, because internet based media have also become “mainstream” in many ways, while print and electronic media outlets have also created substantial digital footprints blurring this binary.

- See https://schoolsforchiapas.org/wp-content/uploads/2014/03/Fourth-Declaration-of-the-Lacandona-Jungle-.pdf